The Geologic History of Sandia Mountains and the Albuquerque Basin

When we moved to New Mexico, I though we would miss seeing Mount Konocti. Lucky for us, we have a lovely view of the Sandia Mountains instead. The Sandia Mountains are a popular destination for outdoor enthusiasts, offering opportunities for hiking, climbing, and enjoying the scenic beauty of the area.

The Sandia Mountains

Sandia Mountain is a prominent feature of the landscape in Albuquerque, New Mexico. It is part of the Sandia-Manzano Mountains. The mountain range gets its name from the way it looks, especially in the light of the setting sun. Sandia is the Spanish word for watermelon. The line of green trees bring to mind the rind of a watermelon, with a beautiful pink glow of the mountains on the red and pink rock resembling the sweet fruit.

While the range was once thought to be part of the Rocky Mountains, they actually formed in a completely different way and much more recently than the Rockies. Although the Sandia Mountains are geologically very young mountains, they contain very old rocks.

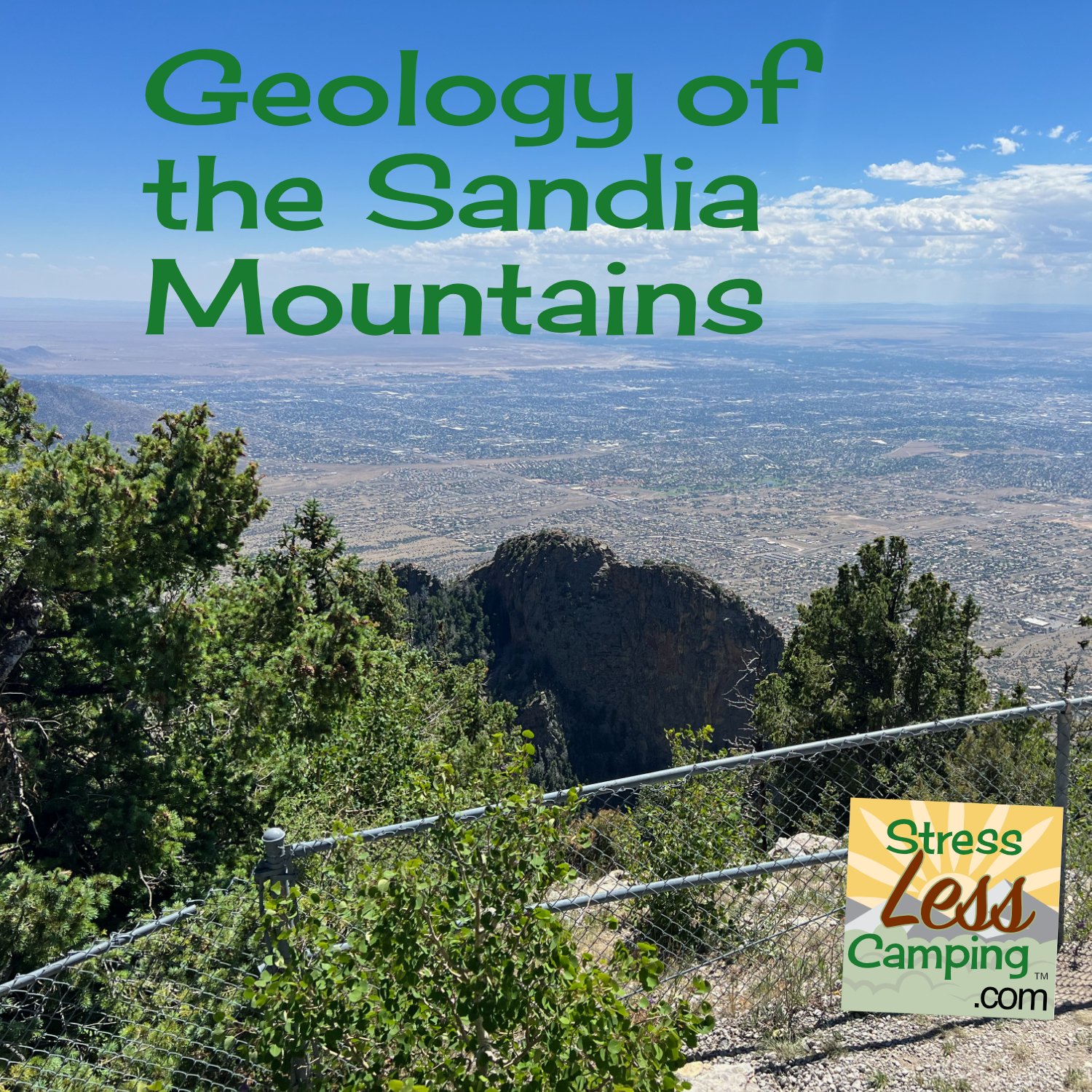

Tony and Peggy take in the view of the Albuquerque from the Sandia Crest lookout

Very old rocks

Let’s begin at the beginning. The bulk of Sandia Mountain consists of rocks that are over a billion years old. Primarily, the rocks are granite, which is igneous, and gneiss and schist which are metamorphic. Th… question in the back?

Meta-what now?

Oh, I did say the beginning, didn’t I? Ok, quick intro to rocks. There are three categories of rock. Igneous rocks are solidified magma or lava, which come from volcanoes. Metamorphic rocks have undergone transformation by heat, pressure, or other natural agencies. Sedimentary rocks are formed by deposits, or sediments, that built up and then became solid as water passed through and left cementation minerals to hold them together. OK? OK.

Metamorphic and Igneous

Alright, so, the metamorphic rocks are the oldest in this mountain range. They are about 1.6 billion years old. About 1.4 billion years ago, granite formed when volcanic magma cooled slowly, deep below the surface.

These ancient rocks were uplifted and exposed during the mountain-building processes that occurred during the Laramide orogeny, a period of mountain-building that took place roughly 70 to 40 million years ago.

Why is there volcanic magma hanging out in New Mexico, you wonder? Well, tuck away the word rift, and we’ll get back to it in a moment.

Today, the metamorphic gneiss and schist is mostly found on the north and south ends of the range. The granite pushed its way up through those rocks, and that’s what makes up the bulk of the mountains now. What caused that push, raising the mountains a mile above the rest of the area, you wonder? Again, I ask you to hold on to the word rift.

Sedimentary

At the prominent ridge of Sandia Crest, layers of sedimentary limestone, sandstone, siltstone, and shale are visible on the western side of the mountain. The sandstone is primarily red and pink in color, while the limestone is lighter. This is why we can see the bands of colors from far away. The oldest layers contain fossils from a shallow sea that covered most of New Mexico about 320 million years ago. These layers are called the Sandia Formation and were deposited in a coastal environment, with rivers flowing into a shallow sea. The sandstones represent ancient river channels and deltaic deposits, while the conglomerates are composed of rounded pebbles and cobbles that were transported and deposited by fast-flowing rivers.

Above the Sandia Formation, there are additional layers of sedimentary rocks, including the Madera Formation and the Los Moyos Formation. These formations were deposited approximately 250 to 66 million years ago. They consist of shale, limestone, and sandstone.

These upper sedimentary layers are tilted to the east, so the layers are visible from the west but not from the east.

Where did the time go?

Did you notice that we switched from billions of years to millions of years? The sedimentary rocks at the crest are significantly younger than the granite base. The contact between these rocks represents nearly a billion years of missing time. This is called an unconformity and this is part of a very wide-spread gap in geologic history, known as the Great Unconformity, which is still a mystery to geologists.

The Rio Grande Rift

I guess I’ve teased you enough. I promised you’d see the word rift again, so here we go.

A rift is an area in the earth’s crust that is pulling apart and thinning. A rift is different from a plate boundary, because it is within a plate. Sort of like a large fault line, a rift pulls away from the center line and stretches the crust. In fact, the Rio Grande Rift are bounded by fault lines. The Rio Grande Rift stretches from Mexico into Colorado.

The rift began to form around the same time as the Basin and Range formation in the west. That was about 20 to 25 million years ago.

The center of the rift, where it’s thinnest, is where we see as the long, low basin including Albuquerque. This thin area is also where the Albuquerque Volcanoes erupted, about 200,000 years ago. While that seems like a long time to humans, it’s really pretty recent in geologic terms. Geologist consider the rift region to be dormant, but not extinct. In fact, new volcanoes could form along the fissure line.

The Albuquerque-Belen Basin contains about 20,000 feet of loosely consolidated sediment called this the Santa Fe Formation. The rock layers visible at Sandia Crest were once continuous with rock layers that are now tens of thousands of feet below Albuquerque. Movement along the fault lines bordering the rift lifted the mountains to about 5,000 feet higher than the valley below.

The rift itself appears to be continuously moving at about 2 millimeters per year. While this small, slow moment doesn’t seem like much, it is enough activity to keep geologists interested in studying the movement to help determine any hazards that might result. It’s also unknown if the rift will continue to spread, or if movement of other of Earth’s plates will cause it to cease forming.

Erosion

Over time, erosion has played a significant role in shaping the landscape of Sandia Mountain. The steep canyons, rugged cliffs, and deep ravines seen today are the result of millions of years of weathering and erosion by water, wind, and ice. That sediment I told you about, the Santa Fe Formation, that filled the basin came from the erosion of the mountains and from volcanic eruptions.

Not erosion

Typically, rivers are caused by erosion by continuous movement of water. The Rio Grande’s pathway was not formed by erosion. Instead, the river has followed the path of the Rio Grande Rift for the past three or four million years. The river meandered throughout the valley, and help with depositing some of the sediments in the valley. Erosion form the Sandia Mountains is keeping the river level from eroding deeper now.

Groundwater

Much of Albuquerque’s current water supply comes groundwater trapped in a sand and gravel sediments within the Rio Grande Rift. The term for groundwater trapped below ground is an aquifer. Aquifer water, which the city uses for drinking water, was likely collected thousands of years ago. The Earth cannot make more water. All the water the planet has is either on or below the surface, or in the atmosphere waiting to be turned in to rain to return to the surface in what’s known as the water cycle.

While there might be a lot of water below the surface, not all of it is suitable for human use. The thickness of the usable aquifer below Albuquerque is about 500 to 1,500 feet. There is a limit to the amount of water we can extract from the ground for our use. The top of this usable aquifer, or the water table, is anywhere from 15 to 1,000 feet below the surface. Deeper, the water may be trapped in rocks that are too difficult to extract from. Additionally, the minerals dissolved in the water increases with depth to a point that it is not longer healthy.

Visiting

You can get to the peak of the Sandia Mountains by vehicle from Albuquerque. It’s a relatively short ride from this major city. If you get accustomed to the desert setting that is Albuquerque you might be surprised by the pines that surround you in less than a half hour’s drive.

One more thing - on the road to the top you’ll absolutely want to make a stop at TinkerTown Museum - an incredible collection of miniatures and more that we wrote about in this story.

Thanks to New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science for their Brief Guide to the Geology of the Albuquerque Metropolitan Region.